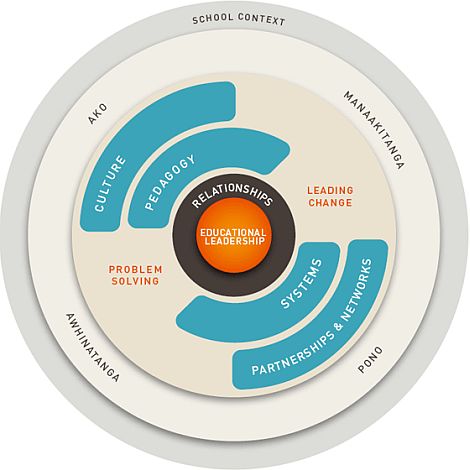

A model of educational leadership

This educational leadership model sets out the qualities, knowledge, and skills principals need to lead 21st century schools.

Elements of the model

Educational leadership

Educational leadership is at the centre of the model. Educational leaders lead learning to:

- improve learning outcomes for all students, with a particular focus on Māori and Pasifika

- create the conditions for effective teaching and learning

- develop and maintain schools as learning organisations

- make connections and build networks within and beyond their schools

- develop others as leaders.

School context

Different contexts can present different challenges for school leaders. As educational leaders, principals need to adapt or adjust their leadership practices to meet the particular demands of school context.

Manaakitanga, pono, ako, and awhinatanga

Effective school leaders demonstrate these four qualities. They are essential for school leaders who are focussed on educational leadership.

Leading change and problem solving

Leading change and problem solving are key activities of effective educational leaders.

Culture, pedagogy, systems, partnerships, and networks, bounded by relationships

School leaders work across these four interconnected areas of practice. In order to be effective, they must be knowledgeable and capable in all. Quality relationships are pivotal to effectiveness in all four areas.

The importance of relationships

Building trusting and learning-focussed relationships within and beyond the school is central to the principal’s role (Bryk & Schneider, 2002). Relationships built on trust are developed when principals respect and care for others and consistently “walk the talk”.

Principals can benefit from personal reflection, sharing ideas and initiatives with their peers, and working with others to clarify situations and solve problems. Relationship skills are embedded in every dimension of such actions and involve much more than simply getting along with others. They play an important part in managing conflicts of interest, supporting and challenging teacher practices, and dealing with a range of challenges and situations.

Educational leadership and leading change require principals to communicate clearly their intentions to teachers. The more principals focus their relationships with teachers on the core business of teaching, and the more they communicate goals and expectations about quality teaching and learning for each student, the more effective they are likely to be in leading their schools towards improved student outcomes for all. Moreover, integrating staff considerations in the development and implementation of school practices is central to making significant shifts. Effective principals get the relationships right and tackle the educational challenges at the same time — incorporating both, simultaneously, into their problem solving (Robinson, 2007).

The relationship principals have with their boards of trustees is especially important. The principal has a unique constitutional role in being both a full member of the board and its chief executive. Among other responsibilities, the principal and the board of trustees are jointly responsible for setting the educational direction for the school and its goals for student learning. The principal’s task includes providing the board with evidence-based analysis of student learning and evaluative reviews of school practices that help inform future action.

Principals know how important building and sustaining good community relationships is to the well-being and culture of their schools. Relationship building prepares the ground for creating partnerships between the school and its community. When the community engages with the work of the school, the positive spin-offs invariably benefit both teaching and learning.

Improved learning for all students is likely when the principal’s leadership is underpinned by effective functional and interpersonal relationships. These relationships play an important part in enabling the principal to:

- build trusting relationships through active listening, caring for others, and demonstrating personal integrity

- actively lead and participate in professional learning with staff

- manage the delicate balance between supporting and challenging others

- encourage and participate in professional conversations that help teachers to share expertise and strategies that improve student learning

- manage dilemmas when the needs of the students and those of other members of the school community are in conflict

- encourage giving feedback to teachers through regular and documented classroom observations.

The power of context

A key difference between New Zealand and other OECD countries is our particular system of self-managing schools. Our system requires that principals work as chief executives of their boards of trustees to support the development of policy, then take responsibility for carrying policy into practice. This includes setting the direction for the school in ways that reflect the needs and values of the local community.

Different school types, sizes, and communities create different contextual challenges for principals (Southworth, 2004). New Zealand school contexts are more varied than most other OECD countries where, for example, up to 90 per cent of schools are in urban centres. In New Zealand about half of all schools are situated in provincial or rural areas. Forty per cent of New Zealand primary schools have fewer than 100 students, and many have teaching principals. At the other extreme are large secondary schools with up to 3,000 students. In these schools the distance between the principal, staff and students is considerably greater than in smaller schools. The increasingly diverse composition of New Zealand’s student population, accompanied by a widening range of student learning needs, present further challenges. Principals and teachers are faced with developing the school’s capacity to identify, understand and meet those learning needs.

Context has major implications for leadership and management arrangements, professional development, shaping the curriculum, developing learning environments, managing resources, and engaging with communities.

Because principals work within the fabric and politics of the school community, the leadership role extends to the wider community itself. This requires knowing and understanding what is valued by the local community. Then, using skilful relationships and communications, the principal leads thinking around how the school and community might work together to provide students with the best learning opportunities.